Game Review: Spyro the Dragon

- Stephanie Dorris

- Oct 17, 2018

- 4 min read

Spyro the Dragon, a platformer game that was first released for the original Sony Playstation, was an immensely popular and nostalgic game for many gamers. Platformers – games where the primary mechanic of difficulty and advancement in the game is from jumping from platform to platform - were by no means invented with the first Spyro game. However, the graphical capabilities of the 3D rendered world and the imaginative classical fantasy-inspired worlds were influential on the hearts of many gamers who picked up the title for their Playstations. Aside from being well-regarded in the memories of those who played it, the original Spyro the Dragon is noteworthy for having simple controls and combat mechanics while still propelling a player through an expansive world. The ease of play in Spyro de-prioritizes full completion and difficulty as a metric of necessary gameplay while still maximizing player satisfaction and narrative payoff.

Spyro the Dragon’s main plot is simple – an evil Gnorc (whose character design is as obvious a melding of Goblins and Orcs as the name implies) has stolen the dragons’ hoard of gems and turned all adult dragons into stone. Young Spyro, the titular hero, must go rescue the other dragons, regain as much of their treasure as possible, and eventually face Gnasty Gnorc. Functionally, the game is subdivided into thematically organized “homeworlds” that allow you to freely travel to a number of different sub-worlds with their own dragons, gems, and other collectibles. After you collect enough of a particular category of collectible item, whether it be dragons freed or gems collected, a balloonist takes you to the next homeworld – one step closer to Gnasty Gnorc and the game’s end.

Most of the game’s elements benefit in worldbuilding from utilizing what Henry Jenkins would characterize as Evocative Spaces. Notions of dragons, the enemy characters of Goblins/Orcs, and fairies as Spyro interprets them are all already embedded in the Western imagination. Spyro’s relatively straightforward delivery of classical fantasy elements gives way to twists and creative decisions that make the game more lighthearted in tone. For instance, dragons that Spyro saves give dialogue that ranges from straightforward advice to sass about upcoming enemies’ vulnerabilities. Spyro himself is characterized as an eye-rolling, snarky teenager more than a serious hero. Through dissonance with the traditionally more serious high fantasy elements of the game, the narrative and dialogue choices create a tonal shift that lightens the severity and impact of failure in the game without detracting from the feeling of player success when the game progresses.

In addition to the narrative choices of Spyro, the gameplay furthers the ability for player success to feel meaningful and satisfying without a significant ‘negative’ consequence for failure. For instance, all enemies that populate the realms puff into smoke with one simple hit, while Spyro can take four ‘hits’ before dying and respawning. Spyro, to ‘kill’ these enemies, only has two combat mechanics: a simple sped-up horn charge to bash into enemies and a flame breath. Aside from combat, the game’s prioritization of exploration is highlighted by another mechanic – that instead of simply jumping from platform to platform, Spyro can glide and soar in a given direction until he lands by pressing the jump button again. The glide mechanic adds a unique flair to an otherwise traditional platformer, but is more importantly the source of a deeply satisfying mechanic in the game – the player can glide to different platforms and traverse great amounts of levels and viewpoints, making gliding to faraway platforms and exploration much more tempting than combat. The glide mechanic also keeps the player relatively insulated from most falls, and eases the difficulty of jumps.

While the collectible genre has evolved, meshing with current notions of completionism, Spyro offers what might be an early and less familiar take on the expectation of completionism in gaming. The thresholds to get to the next world and advance your quest are remarkably low. If a player were to explore every subworld available to them, they would easily gather all of the necessary collectibles to advance without even trying. On my first playthrough, I remember going to a balloonist and completely skipping the dialogue telling me what I needed to collect, instead getting an offer to travel to the next world. I had already, by nature of exploration alone, freed all of the required dragons.

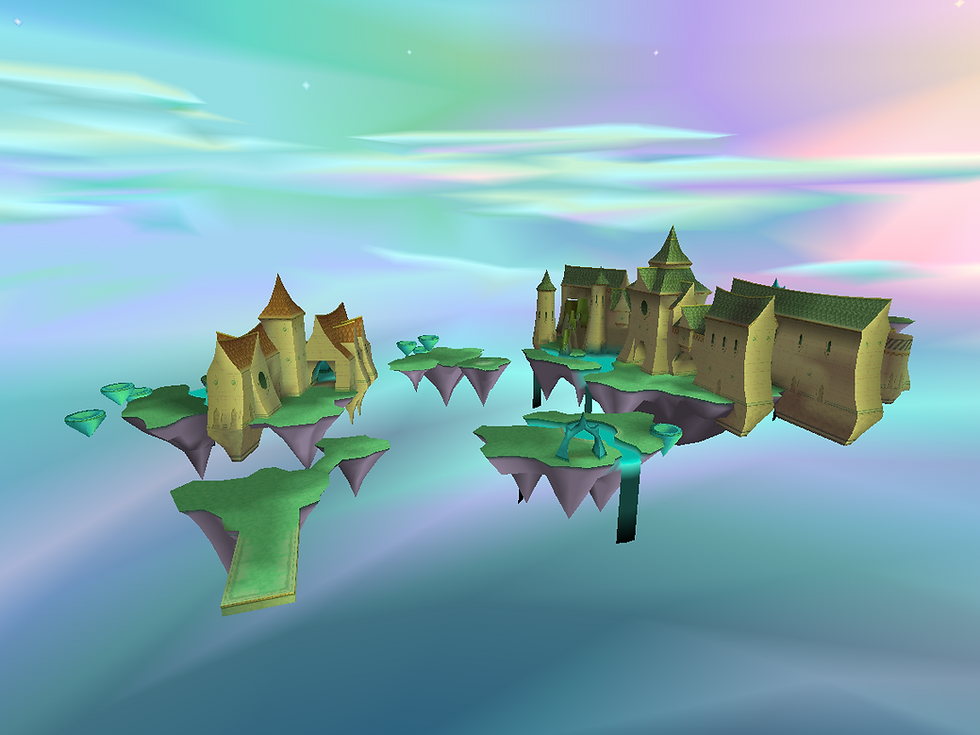

Both the simple gameplay mechanics and the low bar for collectibles in the original Spyro offer up an impression that the game is a sort of precursor to later trends of art and exploratory games instead of squarely a ‘collectible’ game. While the game is perhaps not intentionally coded as feminine, when viewed through the lens of today’s masculine gaming culture and implications of hardcore gaming as being more legitimate, there is something subversive and even freeing about Spyro. The sweeping watercolor pastel skies of the dreamy floating worlds and fairies that kiss Spyro to give him empowered flame breath feel like an escape, a realm where success and satisfaction in gaming isn’t measured by how many of the gems you can collect but instead as an exercise in exploration, simplicity, and joyfulness. While games like Braid overtly subvert and question dominance through thematic elements, a game like Spyro instead seems like it lives by the principles that are not currently dominant in gaming – principles of self-fulfillment and curiosity. In this way, Spyro might not narratively offer a complex commentary on what we value in games and who should play them, but instead shows an example of what a game might look like when developed absent of demands of competition or hard-won achievement as a necessary precursor to gaming.

Sources:

"Game Design as Narrative Architecture", Henry Jenkins

Images:

Ripped image from Spyro WorldViewer by user sleepygem, Mastodon social -https://mastodon.social/@SleepyGem/99123400359456805

Thumbnail from "Retro Gaming - "Spyro The Dragon" - 1998 - PS1" by ShadowGamersFR - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w73pXjhYEMA

Screencap from user sp3000, NEOGAF forum -

https://www.neogaf.com/threads/rttp-spyro-the-dragon-or-the-best-platformer-on-the-playstation-1.495678/

Screencap from Spyro Wikia - http://spyro.wikia.com/wiki/Dream_Weavers

I also totally agree @Stephanie - I think the new art style misses the point. It's also not that increased detail needs to subtract from the colorful open feeling - I don't know if anyone's played Spyro 2 Season of Flame for the Game Boy Advance (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ooA_57RQrTw) but the levels are crowded without subtracting from the fantasy style.

The older one looks much more relaxing.

To illustrate my point a little, here's the exact same castle side-by-side. They just don't have the same color palette or artistic effect on a viewer.

I can't figure out if there's a way to reply to peterforberg's comment, (sorry Peter!) but in response to your question, I have mixed feelings. While I'm really, really excited about it and will probably love playing it again, I'm a little worried that the art style won't necessarily represent a true HD remaster of the original Spyros. I think that this point comes through most obviously in the buildings of Spyro and less the grass/nature flair - instead of keeping the sparse appearance of the original buildings (that seem to be blank not for lack of design but due to the the PS1's rendering capabilities) the developers are fleshing out the buildings and character designs of the dragons. While…

I haven't played Spyro the Dragon in a long while, but I recently replayed Year of the Dragon, and I think that its game play so neatly fits into exactly what you described: there are boxing mini games, skateboard trick mechanics, top down bullet hells, truly a game that took the genre and said, "Let's just have fun with it." Your comment on the subversion through mechanics rings true with the game's ability to create challenges (like the extra percent above 100 to "truly" beat the game) while denying the usual skill-mastery typical of completionist games. Instead, it begs you to play around more. How do you feel about the upcoming Reignited game?