Game Review: Garry's Mod

- peterforberg

- Oct 16, 2018

- 5 min read

Updated: Oct 17, 2018

In 2004, escapism was being mass-produced by a diligent army of online role-players. The past year had witnessed the launch of some industry-defining massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs), such as Blizzard’s World of Warcraft and Linden Studio’s Second Life. Despite their shared acronym, these games came from two very different mindsets: in WoW, one could sink hours into a strict system of leveling, boss raiding, and preset character customization, but in Second Life, players were allowed to build unique, custom worlds using user-generated assets without any pretense (or hope) of exciting game play. And then, in 2006, Garry’s Mod was released.

Garry’s Mod, or GMOD for the uninitiated, has never quite reached the popularity of these towering MMORPGs. A Half-Life 2 mod turned standalone sandbox, it initially functioned much like Second Life, allowing players free reign over a compendium of assets that could spawn vehicles, NPCs, objects, or weapons. It thrived on the modding impetus that a “single game engine may facilitate a wide variety of individual games” and then defied the notion that “mods tend to approach either the visual design of the game...or the underlying game engine”¹ instead of game play. With the addition of player scripts, a cottage industry of user-made game modes flourished, which is how we come to “DarkRP.”

As a whole, GMOD is so vast and unruly that countless game modes exist for every community: highly structured mini-games like “Murder” offer online versions of social espionage party games while incredibly niche role-playing servers like “PonyRP” give enthusiastic fans of TV show My Little Pony the opportunity to experience a “ponypocalypse” where humans are no more. “DarkRP” challenges all of this, seeking unpredictable yet uniform game experiences in a narrative desert. For the purpose of this review, it’s a case study of how a sandbox game can generate a metagame worthy of its own dedicated player base while proposing the development of new, interesting MMORPGs.

“DarkRP” servers are united by shared mechanics with varying customization options. Generally, players are allowed to choose different jobs, each of which give the player some set amount of money over time and grant certain abilities (for example, police officers can arrest other players). Some jobs even require elections from the server, such as the mayor. The base “DarkRP” server is just an elaborate game of cops and robbers with some weird elected bureaucracy and morally ambiguous gun dealers. But most servers incorporate additional roles, ranging from pizza delivery boys to DJs to drug manufacturers. Once a player has acquired a job, they typically want property, which can be purchased in the form of storefronts, apartments, and vehicles. These purchased items can be customized, usually by spawning “props” such as couches or oil drums. And now the staging is clear.

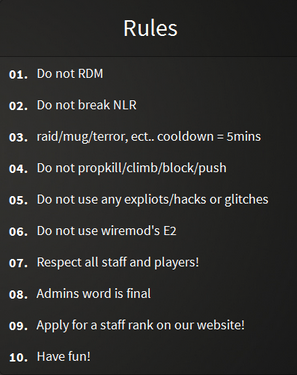

Players perform roles under a simple motivating plot using their “props.” From the Greek word for “to look at”—“theorein”—comes “theatre” and “theory,” and from “DarkRP” we are able to theorize a whole new stage for online role-play. Like any good performance, “DarkRP” binds its community in rules, shared experience, and shared expectations. It goes beyond this to develop shared communication: acronyms such as RDM (random death match) and NLR (new life rule) insist that we buy into the collective fiction of our homebrewed world. These terms become fixtures in servers’ “Community Guidelines” that instruct players on how to perform their roles. The illusion of reality is supported by simulated aspects of reality that are either ingrained in the rules—wages, jobs, elections, power dynamics—or supported by ultimately fruitless role-play—the group of people who design a pizza shop, sell quantifiably useless pizzas, and choose to go along with the story when their shop is inevitably robbed. And, if they defy this by returning to their shop upon respawn, they’ll be bombarded with cries of “NLR”—yours is a new life, so play it instead. Administrators and moderators then respond, and order is returned to the performance. A mimesis spawns from a game that rejected realistic imitation and ignored story, a game with uncanny character models and absurd props stolen from a sci-fi FPS. When given the choice to do anything, be anything, players decided and enforced that they would be human, creating the rules of performance for themselves.

“DarkRP” suffices as an examination of GMOD—at the time of writing, 71% of players were playing dedicated RP and only 6% were in sandbox, the game’s original purpose. Garry’s first attempt at this game used existing SDK to create a melon-launching bazooka,² but his service didn’t get its footing until the tools to create narratives, worlds, and characters were placed into the player’s hands. GMOD proves Myer’s claim that “Over time, because of the mechanical necessities of video game hardware (and because of the consensual necessity of a common set of game rules), video games have tended to culminate more often in the simulative...”³ As we confront the age of virtual reality headsets, the growing population of tech-savvy players, and the increasing demand for mods even on consoles, we can turn to GMOD as an example of what these players can get out of a game. A recently released MMORPG, VRChat, offers “infinite possibilities” but is actually just a reskinned Second Life. Sure, in your VR headset you can wave your arms around to create fireballs, but that’s not a game, and that’s not a game that can stand the test of time when Rockstar is creating a narratively-driven diet simulator in a Western shooter. GMOD, in its base form, isn’t really a game either. In fact, that title, Garry’s Mod, assumes what players expect: it’s an experiment, a personal one, that is constantly changing, that is constantly altering its structure and world in order to develop something greater than itself.

GMOD challenges players to design their own games and to create their own stories, while giving them the tools to do so. A strong community acts as the general will, pushing players to enforce rules and follow the social order. This is important because it reminds us that players still want constraints, but that they also love the ability to create these constraints. Of course, the flaws of this mission are evident: GMOD provides no hierarchical framework for creating quality content, which can lead to toxic communities, limitations on user designs, excessive griefing, and a general lack of uniformity or consistency that shortens the number of hours spent in-game and makes it inaccessible to those not already aware of the community. Players shouldn’t expect to get the curated narratives of popular RPGs, nor should they expect the satisfying, systematic grind of an MMO. The purpose, then, of GMOD, is to receive the unexpected by engaging with the vast set of possible experiences it can give you. Most mods involve individuals making what they want, but GMOD invites many individuals to participate twofold: changing the game, and then experiencing it anew with the assistance of thousands of other players. It’s not a game; it’s a theory for a world that we can collectively create.

References

1. Galloway, A. R. (2010). Countergames. Gaming: Essays on algorithmic culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

2. Pearson, C. (2012, August 29). A Brief history of Garry's Mod: Count to ten. Retrieved October 16, 2018, from https://www.rockpapershotgun.com/2012/08/29/a-brief-history-of-garrys-mod-count-to-ten/

3. Myers, D. (2009). The Video game aesthetic: Play as form. Taylor and Francis.

@davidmatz I do admit that the barrier for entry is high. I purchased the game on after watching a group of YouTubers play it when I was ~12. On my own, I couldn't figure out how to install addons, find good servers, or really make the game enjoyable. It wasn't until about 3 years later that I met some people who played regularly, engaged in the emergent narratives, and could guide me through the community.

But what you say about its potential influence on linear, narrative games is interesting to me. I feel like, as AI grows more sophisticated, allowing players more options in a confined space that still has lots of unpredictability could raise the bar for what games…

Correct me if I'm wrong because I've never played Garry's Mod and don't think I have the time to get over the initial hurdle you described, but it sounded like people really buy in to the narratives, which was impressive to me because I feel like in a lot of games where you can do cool or hard stuff narrative takes the backseat. It was especially surprising considering how there's no narrative inherent in the game itself; it's just a sandbox with artificial stories. But it actually sounds like the player driven aspect makes the narrative more compelling rather than less.

In a game like BioShock there's this linear narrative the creators put you through. It's an interesting story and…