Game Review: Harvest Moon (1997)

- kaedmiston

- Oct 18, 2019

- 5 min read

Natsume’s Harvest Moon was initially released for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System (SNES) in June 1997 and though it was not the massive commercial hit of the Mario Brothers franchise or Sonic the Hedgehog, Harvest Moon has slowly but surely given rise to an empire of family-friendly farming games. It has formed the basis for an entire genre of farming games and inspired massive commercial hits, such as Farmville and Stardew Valley, based on its gently atmosphere and open-ended design.

The game’s mechanics are intuitive to a player who understands the SNES controls, but even the how to play screen declines to explain exactly how to work the controller for the game specifically. Indeed, the form of Harvest Moon is essential to its message of an entrepreneurial farmer looking to find his own way in the world. Each tool has an explanation for its use in the journal, but no specific instructions (for example, press A to move dialogue or Y to use tool.) This forces the player to experiment and learn along the way. A key message of Harvest Moon is this “do it yourself” attitude that encourages the player to find their own way in the world. It mirrors the format of the game in that way. The player controls a young boy who has been given his grandfather’s decrepit old farm and is now tasked with making it a viable operation with crops and livestock. The player starts with all the essential farming tools (though none of the livestock) and learns on the job, so to speak. Beyond the precious little guidance on the tools available in the game, the player is also deprived of knowing what time it is in the game or how much stamina is left. Because there is both a limited amount of time and stamina, the player must budget accordingly, but the player is never given any indication of how much is left. There are sign posts of when the boy gets tired, such as when he wipes his brow or eventually falls over, no longer able to do any more work, but the player is responsible for the internal calculus. Moreover, there are happiness points that measure how happy the boy is, but the player is never alerted of this quantity or how to improve it (such as making your wife happy or hugging your dog.) Curiously, this increases the replay value of the game, as the player is able to keep learning through new plays about different ways to make the young boy happy.

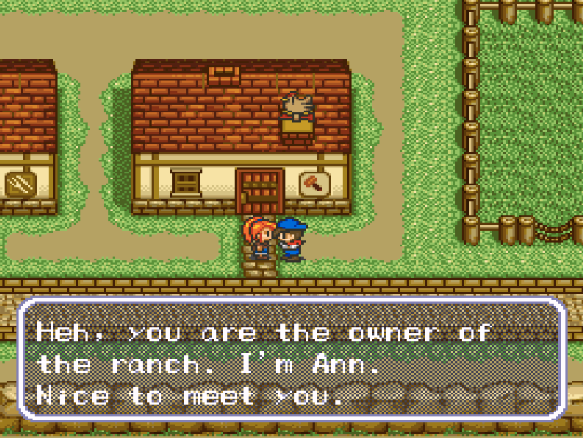

The player’s relationships with the nonplayer characters (NPC) follow this same method of "do it yourself" and "learn it yourself" with the romantic options. Part of the goal to living as a successful farmer is to get married and have children; the player has five options for a potential wife: Ann, the tomboyish inventor; Eve, the tempestuous bartender; Ellen, the animal-loving restaurant owner; Nina, the sweet flower shop girl; and Maria, the innocent local nun. To attract any of the bachelorettes, the player must give gifts that the chosen bachelorette would like. The player can learn this through trial and error, watching her reaction when the gift is given, or by reading the bachelorette’s diary. Yet, none of this is broadcast to the player. It is only when the player accidentally gives a gift or wanders into the home that he or she notices the possibilities.

Harvest Moon gives little in the way of guidance. The player must find a way to earn money, discover the game mechanic to learn how much money is left and what day it is, and is not told how much stamina is left or the time in the day (at least until receiving a clock through a house upgrade or buying one). There is as much guessing and trial and error to Harvest Moon as there is genuine strategy. Its purpose as a game is the experience of learning how to play the game as much as it is trying to rebuild the farm. This allows for different experiences of the game based on the player. A more adventurous player will explore every nook and cranny, trying to discover as much information as possible, while a more conservative player will only gather as much information as necessary to move on and complete the given challenge, whether it be learning how to use the hoe, planting turnips, or romancing the future wife. The most notable impact this difference will have is in terms of the possible endings. Although the player is never told this, the young boy only has 2 years (300 in-game days) to rebuild the farm, find love, and have children. If the player works hard and explores everything to make efficient use of limited stamina and time, the boy’s father will come to inspect the farm and congratulate the player on a good job. If the farm is not up to snuff, the father will scold the boy on his laziness. Yet, the player is never given a timeline for the game. The only option is to play the game with the intent to enjoy the farming experience. This leaves the player with only one thought pattern while playing the game: Are my potatoes doing well? Did the wild dog kill my chicken last night?

At its heart, Harvest Moon is a game about a simpler life, where hard work always reaps rewards and you can easily find love by giving your interest gifts. Rather than being an ironic commentary on the drudgery of a life before large city living, Harvest Moon is a response to the growing global commercial and urban atmosphere. In a world of increasing technology and integration into society and two years before The Matrix is released, Harvest Moon is a call to a simpler time. It asks the player to explore the world and learn about the sometimes-tedious job of being a farmer, grappling with limited resources and precious little information. Yet, instead of boring the player, Harvest Moon’s gentle way introduction of the player to different concepts and encouragement to explore allows the player to imagine him-or-herself as the young boy trying to revive his grandfather’s farm. There’s no specific purpose to the game, especially in the first playthrough before you learn about the father’s arrival and judgement, just a call to enjoy farming and the world of Harvest Moon. If a person has the time and willingness to devote, Harvest Moon will reap as much fulfillment as it will potatoes and tomatoes. Yet, it will never be a gigantic commercial success on the par of Mario or Sonic because Harvest Moon asks of the player more. It asks the player to find their own meaning and a world large enough to develop that meaning for the player themselves. Instead of having some predetermined purpose to which the game is pointing the player, the game leaves it far more open. “Why am I doing this?” The player asks. Harvest Moon responds: “Because you want to.”

Works Cited:

“The Matrix.” IMDb, IMDb.com, 31 Mar. 1999, www.imdb.com/title/tt0133093/.

Comments