Game Review: Space Invaders

- Charlotte Wang

- Oct 17, 2019

- 4 min read

Tomohiro Nishikado’s Space Invaders (1978), a renowned retro arcade game, is said by some to have revolutionized video games, with its success contributing to the global expansion of this industry. The premise of the game is simple: as the player, you operate a small laser canon with the objective of destroying ever approaching aliens in order to get the highest number of points possible. Once you defeat all of the aliens on one level, you progress to the next, and so on. The simple satisfaction of shooting your laser and hearing the explosion of your enemy makes the game highly addictive and contributes to its overall success.

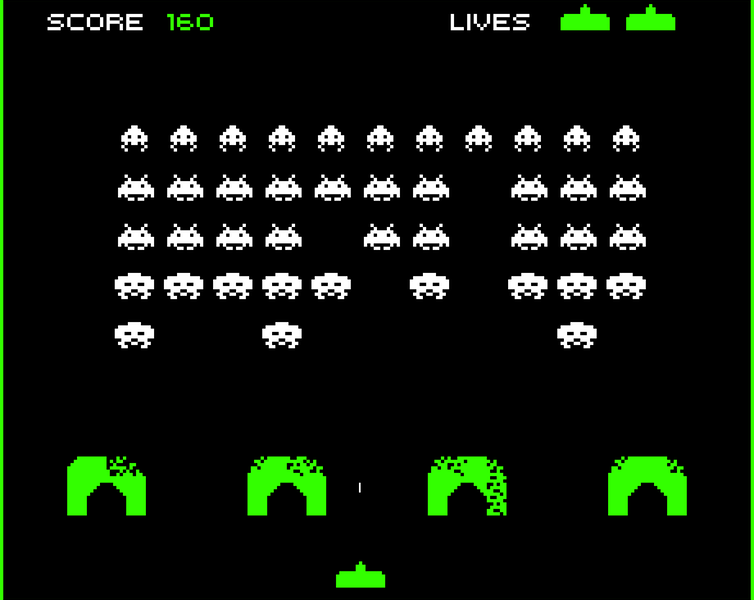

While playing, however, I began to think more about the environment of the game and what affects it affords to the player. In terms of aesthetics, the overall appearance of the game lends itself to a feeling of discomfort. Even in the title of the game, “space” establishes the uncertainty of the location, and “invaders” establishes the unknown of the other characters in the game. The black background, in accordance with the idea of being in space, shrouds your surroundings. You are immediately presented with the discomfort of being in an unfamiliar place with a collection of unfamiliar foreigners gradually approaching and attacking you. In the first level, you and your protection are the only things in green, while the invaders are all identically white. The characters, none of which look like you, all look remarkably similar to each other despite minor variations. Playing the game, you hardly notice the small differences between each of the white aliens. Their outlines are unrecognizable to you as they do not look like any animal or human you might have seen on earth. In their formation, they lose any sense of individuality, and they all become a common enemy that you want to destroy.

The visual aspects of this game led me to think about how different races and cultures in our societies view each other. Growing up as an Asian American in the United States, I have encountered many experiences in which I felt like I was confused for or viewed similarly to other people simply because we were both Asian. When a culture is unfamiliar with a new type of person, they simplify their confusion by categorizing them all together. Everyone is further dehumanized when races and countries are at odds with one another, and there are outbreaks of war. We stop thinking of the other country as a collection of individuals and begin to see them as one common evil. While playing Space Invaders, it was scary to imagine how easy it is to feel this same way about the aliens we were set out to destroy.

I began to think more about what the game’s mechanisms add onto this initial thought. In terms of what the game allows us as players to do, we are essentially trapped into one horizontal line of movement. We can move left or right and shoot. When we destroy, we are rewarded. There is no possibility to approach the enemy, nor is there the ability to escape. The only action we are given besides movement is to shoot. We become trapped in this anticipation, forced to fight the enemy. The invaders themselves move back and forth across the screen, approaching us. They gradually move closer to the bottom, with the sound of four decreasing notes in the background getting faster as time passes.

What the mechanisms led me to consider is how we are born into societies with the inherent structural desire to be exclusive and dislike others. When approached by the enemy, our immediate reaction is to assume the worst, that they are programmed to attack us and that the only possible way of dealing with these invaders is to attack yourself. Just as the menacing four-tones are embedded into this game, our societies themselves lead us to these implications. These menacing aspects of the game are not the choice of the player and likewise, these feelings of discomfort for others is not the choice of all born into these societies. Living in the United States, where there used to be and still is this feeling of “American exceptionalism,” it is easy to see how we may be immediately programmed to feelings of superiority and distaste for other countries. Many cultures and countries have similar feelings of patriotism, relishing the exclusivity of their group and indulging in the comfort and pride that it affords. These feelings of reliance on the rules in which we were born are natural and are the essence of the Space Invaders game: without question we pick up the controller and do exactly as we are told. It is easy to accept the rules of the game at hand and not question why we are only allowed this one action and this one reward mechanism. Just as the game gives points to those who obey the rules and even greater reward to those who play it well, in our societies we are rewarded socially for obeying the rules of our games. We are more liked for expressing loyalty to our regimes, cultures, and races, and for expressing dislike to others.

Though this game might not have been created for this purpose, it is interesting to take a step back from playing and consider how easy it is to accept the rules that are given and to be not only drawn into but also to find comfort in this reward mechanism. Perhaps this game can lead us to consider how in our own societies we may have developed a reliance on the rules of our games and become too uncomfortable with the idea of others.

Comments