First-Person Bodies

- maesparza

- Nov 3, 2018

- 2 min read

I’ve been thinking a lot about the conventions of first-person shooters and how they play into our understanding of Gone Home’s genre. The content of the game is decidedly atypical of many of the most popular FPS games (chiefly the fact that there is absolutely no “shooting” involved), but in terms of describing the interaction of the player character with the surrounding environment, they’re useful as an initial reference point. The player inhabits the bodily space of a character and moves through space as that character instead of controlling the action of a totally external avatar, as is the case in platform games. We see what the character sees.

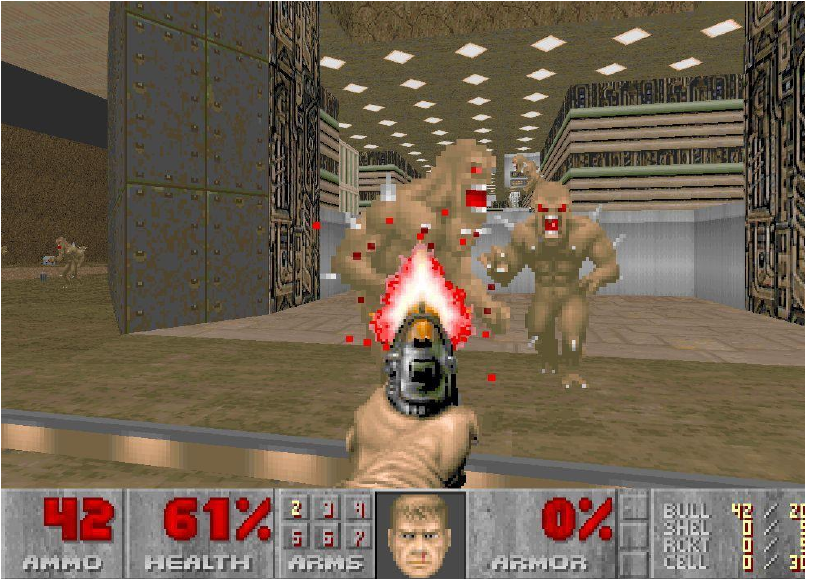

There are things that we don’t see in Gone Home, however, that we typically do see in first-person shooters: namely, the body itself. In almost every FPS game I can think of (Call of Duty, Halo, Overwatch), your field of vision is partially obscured by your character’s weapon or outstretched arm. Even though this is usually the only indication of your own corporeality, it’s nevertheless a concrete visual affirmation of the fact that your character is a body acting on and within a space.

There’s no doubt that your character in Gone Home, Katie, acts on the space of the game and objects within it. You open doors, you turn on lamps, you see how far you can chuck a deck of cards across the hallway (if you’re anything like me, that is). And, through family portraits and passports, you do get a sense of what Katie looks like. In the course of gameplay, however, you don’t catch so much as a glimpse of your own body. When you pick up an object, you don’t see your hand; the object merely sits in midair before you, inert. When you go to open a door, the door swings open, seemingly by its own volition. For a game whose setting is a home, your environment is conspicuously absent of mirrors. While you do mostly adhere to the physics of the real world (you can’t turn on a lamp from across the room), the precise nature of your place within the physical world is ambiguous.

In fact, there are no bodies in the game at all. As far as I can tell, there’s only one confirmation of a body moving through space, and it’s not visual: footsteps. You never see your feet, but you do hear them. So too is the presence of Sam only felt in sound, not in space, through the interstitial snippets of her voice, addressing you as in a letter. There’s nobody to interact with. There’s no body to interact with. You’re temporally removed from the true action of the story, and while you have things to do in the game, they don’t have any real bearing on the course of the main narrative. You’re a secondary (hell, tertiary) character in a story that’s already happened.

Or: you’re not a character at all. You’re the disembodied narrator of an epistolary frame-tale, only involved in the telling of the story, not the story itself. The plot of the game is: you are constructing a plot. First-person shooters are action games. Gone Home, if it is a game, is an inaction game.

After reading your post, I wonder if the game designers intentionally removed the body. If I can crawl into the mind of the designer and interpret, maybe they removed Katie's body to reinforce the horror motifs, making her seem almost ghostly without the body. And moreover, I can remember moving into my parents house after high school or my apartment here. My own sense of bodily sense seemed to dissolve as I took in my new surroundings, mapping and digesting as much as I could. This is Katie's first time in this new house, so maybe its even a comment on the dissolution of the body in a new space; or rather, Katie's lack of awareness of her own body…